If your Chinese ancestors immigrated to North America, you may be able to learn more about them in Canadian or United States records. Here are tips on records that may help you explore your Chinese ancestry.

Chinese Immigrants in Census Records

Chinese immigrants may appear in censuses, which are descriptive counts of the population. You may discover valuable information, such as a relative's occupation and approximate year of birth and when the relative immigrated. Because most early Chinese immigrants were male workers who left their loved ones behind in China, you won't often find them enumerated with their families.

The United States has taken national censuses every 10 years since 1790. Chinese immigration became significant after the California Gold Rush began in 1849. Chinese ancestry was first noted in the California census of 1852.

In Canada, national censuses have been taken every 10 years since 1871 and every 5 years since 1971. Most early Chinese immigrants to Canada went to British Columbia. Census records in British Columbia began in 1881.

In both countries, Chinese residents were sometimes missed, or their information was written incorrectly. Sometimes Chinese residents avoided census takers. At other times, language and cultural barriers were to blame.

Finding Vital Records (Births, Marriages, and Deaths)

Records of individuals’ births, marriages, and deaths have been kept by different North American government offices at various times and places. In Canada, these vital records are called civil registration records and are kept by individual provinces. Civil registration began in 1872 in British Columbia; Chinese residents weren’t officially included in these records until 1897. This guide to civil registration records for British Columbia includes links to free FamilySearch collections.

Individual states and counties in the United States may have marriage records dating back to when the state or county was organized. Birth and death records weren’t reliably kept in many places until the late 1800s or early 1900s.

In both countries, Chinese grave markers may provide additional information about relatives. Tombstones of immigrants may include the deceased’s name and maiden name and that person’s Chinese province or district and village of origin (and, for married females, similar information about her spouse). Several Chinese cemeteries in California, British Columbia, Hawaii, and other locations are documented on Find A Grave. Tombstones and in other Chinese-language records may use dates specific to the Chinese calendar.

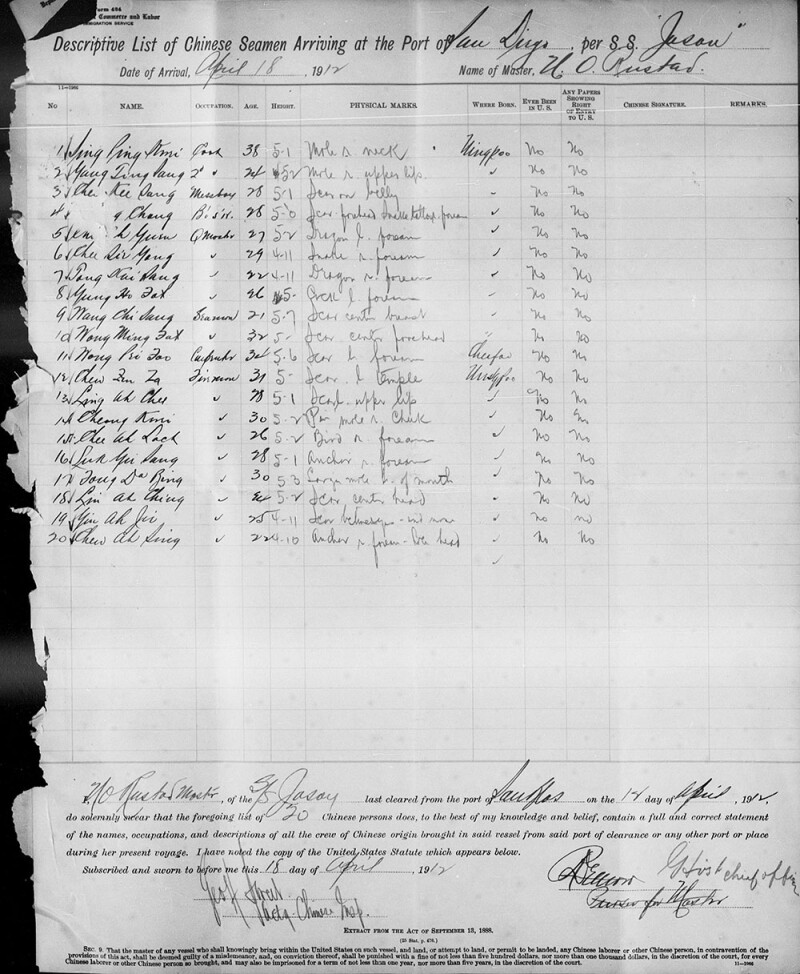

Chinese Immigrants in Passenger Lists

Chinese immigrants to North America generally landed at West Coast ports. In the United States, San Francisco and Hawaii were the most common destinations. In Canada, look for Chinese passengers arriving in Vancouver, Victoria, and other ports in British Columbia.

British Columbia passenger lists don’t begin until 1905, well after the initial surge of Chinese immigration. A collection of Chinese passenger arrival lists for Vancouver (1906–1912, 1929–1941) is available on Ancestry.com and in the Ancestry Library Edition available at family history centers and many public libraries.

According to the Chinese Family History Group of Southern California, in the United States “early immigrants and people in steerage were often not listed by name, but as ‘Chinaman’or not listed at all. If listed on passenger lists after the Exclusion Act, the ancestor was not in steerage, but may have been in second or third class.Travel companions may be listed and their relationship. Women were usually listed with their maiden name and 氏 “Shee” (indicates married woman).”

Several key collections relating to Chinese immigrants are available online:

- Early passenger arrival lists for San Francisco no longer exist. San Francisco passenger arrival lists, 1893–1953 are free to access on FamilySearch.org and include arrivals at Angel Island, which received an estimated 175,000 Chinese immigrants after its opening in 1910.

- Another FamilySearch collection, California, Chinese Partnerships and Departures from San Francisco, 1893–1943, documents Chinese residents who left the United States and Chinese firms doing business in the United States.

- California, San Diego, Chinese Passenger and Crew Lists, 1905–1923 is free on FamilySearch.org and focuses on travelers of Chinese descent.

- The website of the Hawaii State Archive Digital Collections hosts a searchable index to Chinese passenger lists (1843–1900); additional Hawaiian immigration record collections are also available.

For many decades, the Canadian and United States governments kept additional documentation on Chinese residents living within their borders.

Published Histories about Chinese Americans

Even if they don’t specifically mention your relative or family, regional and ethnic history books can help you better understand the experiences of Chinese immigrants and communities. Look for stories about others who may have lived in the same places your family did or who worked in the same occupations.

Look for published histories at your library. If it doesn’t have what you’re looking for, ask a reference librarian for help or search for titles on WorldCat.org, an enormous online catalog of materials at thousands of libraries in the United States,Canada, and beyond. You may be able to borrow a book through interlibrary loan.

Explore the stacks and online catalogs of genealogy research libraries too. For example, the Family History Library holds a copy of Chasing Their Dreams: Chinese Settlement in the Northwest Region of British Columbia by Lily Chow and Unbound Voices: A Documentary History of Chinese Women in San Francisco by Judy Yung.

Learn More about Researching Your Chinese Genealogy:

At FamilySearch, we care about connecting you with your family, and we provide fun discovery experiences and family history services for free. Why? Because we cherish families and believe that connecting generations can improve our lives now and forever. We are a nonprofit organization sponsored by The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. To learn more about our beliefs, click here.