In 1890, the United States conducted the 12th federal census with a sense of excitement. New technologies and strategies aimed to help the 1890 census achieve the best possible results. The census form itself had been dramatically transformed.

Despite all the planning and efforts, the 1890 census was almost entirely lost to future generations. Only a fraction survives, but what does remain is rich in value for genealogists. Here’s what the 1890 census included and how to explore that time period for your family history.

What Was Significant about the 1890 Census?

In the late 1800s, the population of the United States was growing and changing. Immigration was so intense—with nearly 12 million arrivals to the U.S. between 1870 and 1900—that the government opened an enormous facility on Ellis Island in New York Harbor to process them all. Inside the country, residents had been migrating steadily from east to west and were now flocking to urban areas, too.

The job of the 1890 census was to enumerate a body of people who were—literally—moving targets. It was an enormous task, for which an unprecedented 46,408 enumerators (census-takers) were hired. For the first time, enumerators were given detailed maps to help them thoroughly account for an assigned area. A new electric tabulating system would process results more quickly than the 1880 census, for which the count had barely been completed.

What Was the 1890 Census Date?

As with the 1880 census, the official 1890 census date was June 1. This meant that no matter when census-takers actually visited a household, they were to record answers as they would have been on June 1. Any household member born after that date was not enumerated; anyone who had died since then but was still alive on June 1 was to be included. (Since June 1 fell on a Sunday, the actual count began on Monday, June 2, 1890.)

What Questions Were on the 1890 Census?

The 1890 census population schedule introduced a brand new, full two-page entry for each household. Here’s what it looked like:

Nearly every question from the 1880 census population schedule appeared again in 1890. A few new items were asked, including:

- Each person’s middle initial

- “Whether a soldier, sailor, or marine during the civil war (U.S. or Conf.), or widow of such person”

- Expanded race categories: “White, black, mulatto, quadroon, octoroon, Chinese, Japanese or Indian” (new categories were quadroon, octoroon and Japanese)

- For women, “Mother of how many children, and number of these children living”

- “Number of years in the United States,” “Whether naturalized,” and “Whether naturalization papers have been taken out” (the latter indicating whether the citizenship process had begun)

- “Language or dialect spoken,” if not able to speak English

- Several questions assessing health, institutionalization, and homelessness, which were asked in 1880 but in a slightly different way

A special, separate schedule captured further details about those who served in the Civil War and their widows. Details include name, rank, company, regiment or vessel, enlistment and discharge dates, and length of service in years, months, and days. Both Union and Confederate veterans and widows appear on this schedule, but those who served the Confederacy may later have been crossed out.

What Is Left of the 1890 Census?

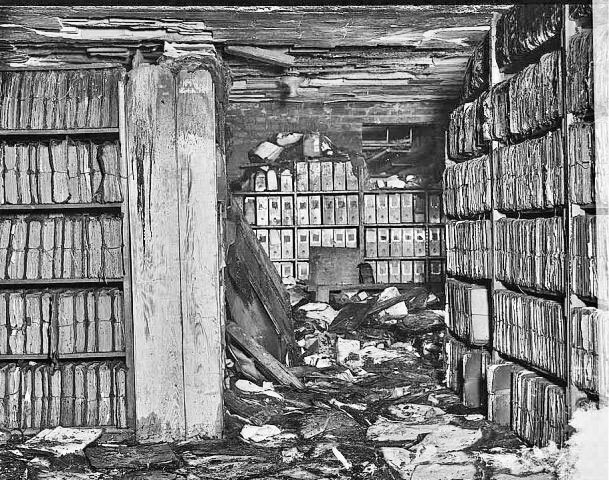

Unfortunately, most of the rich data of the 1890 census was eventually lost. A fire only six years after the census destroyed many special census schedules. Then in 1921, another fire occurred. Most of the population schedules were consumed by flames or were smoke- or water-damaged beyond saving.

However, not all was lost.

A small fragment of the 1890 census population schedule remains, with 6,285 records of the 62,979,766 people originally counted. Those enumerated lived in parts of Alabama, District of Columbia, Georgia, Illinois, Minnesota, New Jersey, New York, North Carolina, Ohio, South Dakota, and Texas.

Enter the names of relatives who were alive on June 1, 1890, especially those who were known to have lived in the above states. Look for entries in the same place that family lived in as shown in the 1880 or 1900 censuses.

Additionally, about half of the Veterans Schedule survives. These are largely for the states of Kentucky through Wyoming (alphabetically).

Again, enter names and locations as best you know them for the time period. When searching for widows’ names, remember that someone who served may have left behind another wife than the one from whom you descend.

If you’re not finding your family in these collections (and many people won’t), consult other records created during or around 1890 as a substitute for census data. City directories, voter registrations, and maps may be available. Use the FamilySearch Research Wiki to help you find them. Subscribers to Ancestry.com can also explore an 1890 census substitute collection, compiled mostly from city directories.

Remember, the surviving portion of the 1890 census is so genealogically rich that it’s worth checking for records of any relative alive on June 1, 1890!

Find Your Ancestor in Another Census

At FamilySearch, we care about connecting you with your family, and we provide fun discovery experiences and family history services for free. Why? Because we cherish families and believe that connecting generations can improve our lives now and forever. We are a nonprofit organization sponsored by The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. To learn more about our beliefs, click here.